When you are at the intersection of Harvard and Thomas and look around, it’s impossible to not be awed and a bit baffled by the utter lack of planning and engineering.

You probably have an intersection that confuses you or an intersection you hate. Leave a comment and we’ll see if we can console you with some sort of reasoning. Meanwhile, here’s one odd truth.

What’s wrong?

Harvard and Thomas… it’s one of a kind. As it heads south Harvard changes from a normal, comfortably cozy Capitol Hill residential street into a confusing mass of concrete with no clear use or direction.

South on Harvard towards Thomas. Harvard Flats is under construction on the left. Westside, completed in 2015, is up ahead on the left. Across the intersection on the right is a 1905 home at 233 Harvard Ave East. Beverly Rae Apartments from 1949 is on the far right. (Rob Ketcherside)

It’s so huge that the Harvard Flats construction has an entire crane in the roadway and no one cares. The construction crew has hidden parking for themselves in the pedestrian detour. U-Haul trucks can tuck away almost out of site. Cars park perpendicular to the street on city land, but you don’t even see them. It would take five or six cars parked end-to-end to block this street.

What were they thinking?

You have to go back to the very beginnings of our neighborhood to understand this intersection.

In 1851, David Denny scouted Alki Point, which became Seattle’s first settlement. He ended up making his home in 1853 on land including and surrounding the current Seattle Center.

Up the hill east of Denny’s land — and to the east of what we now call Harvard Avenue — was the land claim of John Nagle (sometimes “Nagel”). Like Denny’s, the Nagle claim did not conform to township lines of the federal government’s Township and Range cadastral survey. The claims in between them by J. T. Werbun and J. Williamson did conform though, making for oddly shaped and inconsistent properties.

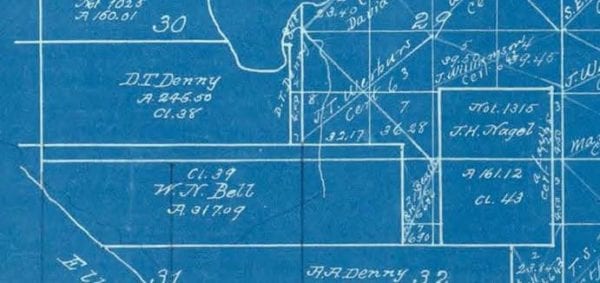

Section of Township Plats, Township 52N, Range 4E. David (D. T.) Denny, John (J. H.) Nagle, and W. N. Bell plats stand out. Between Denny and Nagle was Werbun, with Williamson surrounding Nagel. (Seattle Public Library)

By the 1870s, Werbun and Williamson’s lands were in the hands of Margaret Pontius and her sons. In 1874 Nagle was committed to the Washington Hospital for the Insane and Denny took over management and sale of his land.

Denny began platting his own land out in 1872 and Nagle’s land in 1880. The Pontius family in turn laid out lot lines and named and placed streets on their land, but they disregarded Denny’s efforts. Nearby developers later chose to adopt Denny’s paradigm, Pontius’ paradigm, or in some cases something yet again different.

You can see the effect today all across the neighborhood in each strangely bent street or ajar connection across an intersection. Harvard and Thomas, at the far northwest corner of Nagle’s claim and at the junction of three different plats, became the epicenter for the planning conflict and caused a major headache for the city.

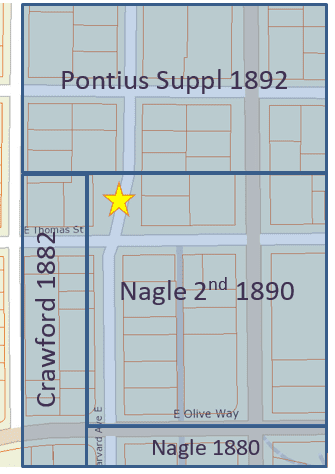

Plats of Thomas and Harvard, showing the intersection location as well as plat locations and dates. Nagle’s 2nd filed by David Denny. “Pontius Suppl” is the A[lbert] Pontius Supplemental Addition plat. Crawford’s 1882 claim actually went further west, ignoring Boylston Avenue. In 1900 the Harvard Heights plat fixed Boylston for the block south of Thomas.

Where the streets have too many names

Let’s focus on the streets themselves.

Seattle’s street names were ridiculous early on. There was no order and no consistency. In 1895 the street names of Seattle were rationalized and drastically reduced in number. That’s when this intersection became “Harvard and Thomas”.

In Nagle’s additions, Harvard was called Villard Street. When Denny named it in 1880, Seattle still hoped to be the coastal terminus of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Henry Villard was its president. Seattle had a Villard Hotel and it had three different streets named after him, all to try to impress him and beat out Tacoma. In the early 1890s the Northern Pacific chose Tacoma anyway, and as a result Villard was erased from our map.

Thomas was named Chester for unknown reasons by James Crawford in his 1882 plat. Perhaps it was U.S. President Chester A. Arthur. Denny continued this name along Nagle’s plats, ignoring the Pontius family’s numbered east-west streets in the Cascade neighborhood. Oddly, Denny also ignored the names on his own plats that lined up with Nagle’s. Far to the west Denny had Thomas Street right in line with Chester.

The name Harvard originated in the Pontinus family’s A. Pontius Supplemental Addition. It’s likely named after Harvard University, but for unknown reason.

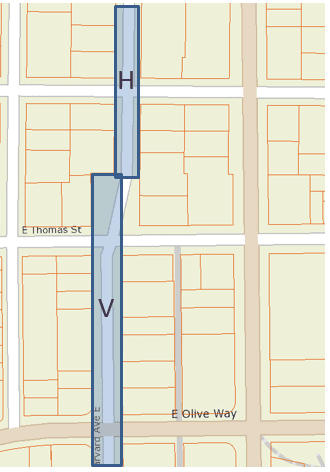

Villard Street was laid out in the box with “V”. Harvard Street with “H”. They hardly connected.

Bureaucracy to the rescue

At the start of 1892, the Board of Public Works and City Engineer went about determining how to level out the street and put in sewers, trees, and lights to make Harvard and Villard attractive places to live. They quickly realized the connection between the streets must be fixed.

The City Council rushed out Ordinance 2015 to enable the BPW to purchase 43 feet off the east side of Villard to allow Harvard to continue straight south to Thomas. It said in part:

… Harvard Street, … at its Southern end, does not correspond in its full width, with the North end of Villard Street, … there being but a narrow passage way from each into the other, not exceeding fourteen (14) feet in width; and … such passage way destroys the continuity of said Streets, and their usefullness [sic] and convenience in a public highway. (Ordinance 2015, March 1892)

In the end, David Denny gifted the 43 foot wide chunk of land to the city as a continuation of Harvard and the plats were united at last.

Broadway area’s first urbanist intervention

Still, the city had a problem. Now they had a triple-wide street. Side streets in this area were and remain today 25 feet curb to curb. They were suddenly faced with 75 feet between curbs over a stretch of about 150 feet of roadway.

Within a month the Park Board was pulled in to help out the street engineers. On April 4, 1892, the board requested Superintendent James Taylor to evaluate adding a park in the intersection of Villard, Harvard, and Chester.

The intersection of Harvard Avenue and Thomas Street seen in a 1904 plan for adding granite curbs (top left), 1936 aerial photograph with tree in Harvard Place Park (top right), 1960 aerial with island park removed (bottom left), and 1988 plans for traffic circle and curb bulbs (bottom right). (All from SPU Engineering Vault except 1937 aerial from King County Map Vault)

James Taylor was the city’s first park superintendent, indicating how early this story is in the development of Seattle’s parks. This park became the Broadway area’s first park of any kind. Lincoln Reservoir was under development, but the earliest form of Cal Anderson didn’t open until 1901.

In 1909 the Parks Board officially named the island Harvard Place Park, but the name was in use by 1899.

Bureaucracy after all

The parklet served the neighborhood well for many decades. As carriages gave way to automobiles and vehicle speeds increased the original plan was tweaked many times. The curb lines of the park slowly changed.

Eraser scars and layers of ink indicate many alterations to Harvard Place Park’s outline from 1892 onward. (Profiles scroll of Harvard Avenue at SPU Engineering Vault)

The park fell on hard times during the Great Depression. One woman tried her hardest to get the city to fix it.

Nan B. Ellis, manager of the Roycroft Apartments to the north of the park, wrote letters to the city several times throughout the 1930s. Finally she got the attention of the City Council in 1939 and a full review of the situation was undertaken.

One thing uncovered was that the Parks Board could not be forced to take care of the park anymore. A May 20, 1931 memo summarized the issue:

Diligent search of plats, ordinance, resolutions and other public records fails to locate any evidence of official action authorizing the establishment, improvement, or other recognition of HARVARD PLACE, or transferring the same to the jurisdiction and control of the Park Department. (Sherwood Parks History, Harvard Place file)

Somehow there was a serious screw up in 1892. First, the city forgot to actually take ownership of the 43 foot slice on the east side of the street. They realized their mistake in 1910, and filed an ordinance to formally accept the gift of Nagle property. Ordinance 24245, less than seventy words long, must be one of the briefest of our city laws. After officially taking possession of the property, they forgot to assign part of it to the parks department.

In 1939 City Engineer C. L. Wartelle told the City Council, “There is evidence that [Harvard Place Park] is extensively used by children as a play area. It could be made quite a beauty spot.” (May 1939 letter in Harvard Place file)

That was not enough to release funds to improve the park, though. Later in 1939 the Streets & Sewers Department wrote back to Nan to say, “We are compelled to advise you that the limited funds at our disposal do not permit us to perform any work on parking strips or public areas similar to the one in question… [We] are seeking the cooperation of the public at large in this endeavor and suggesting that they modify their demands…” (July 1939 letter in Harvard Place file)

All good things come to an end

The park was barren, and it was about to get smaller and then disappear entirely.

The lot on the west side lay undeveloped for half a century. It was informally adopted into the park, adding to the experience. Then finally in 1949 the Beverly Rae Apartments were constructed there, partly sited on the most northwestern parcel of Nagle’s land claim.

And then at some point the park was paved over. It was definitely still there in 1946, visible in aerial survey photography. It was removed by 1960, replaced with concrete in the next survey. Perhaps the trees were cut down concurrent with the construction of Beverly Rae.

Regardless, removing the park may have removed the headache of park maintenance, but it didn’t fix the intersection. In 1988 SDOT took another approach and made the intersection itself safer with a traffic circle and large curb bulbs. But that has only made the massiveness of the street more obvious.

Bringing a park back to the middle or side of the road would be nice. As long as it’s open to cars, we probably can’t turn this into Pac-Land. Something that can draw in neighbors on their way to the library or train station, though, would be welcome.

Do you have a creative idea for at least temporarily fixing the 125 year old problems with this space?