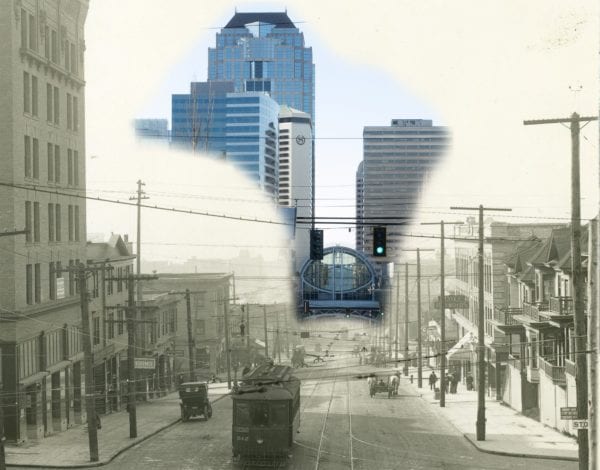

Pike Street west from the edge of Minor in 1902 post-regrade blended with yesterday, January 14, 2017. The 1902 image is fantastic and worth seeing on its own. (Washington State Archives; blend by Rob Ketcherside)

John Pike as an old man, from his 1903 obituary (Seattle Times)

John Henry Pike never lived in our midst. But the street named after him cuts the southern border of our neighborhood, and the improvement of Pike Street led directly to the creation of Capitol Hill. So let’s celebrate him and the street he begat.

John Pike

He was born in Massachusetts, probably Springfield, more than two centuries ago: 1814. Like Seattle’s founding fathers he was part of the “Go West” era of American history. European immigrants and young descendants of early Americans alike all moved successively farther west.

After living in western New York for many years, Pike found himself in the early 1850s living with wife and son in the fateful farming town of Princeton, Illinois.

If you find it on a map today you’ll see a cluster of commercial buildings with a road leading out of town to a freeway and a Walmart. Zoom out beyond the residences and the map is swallowed by farmland. Eventually Chicago appears to the east and Peoria to the south.

Good company

But it had significance to us. In 1852 Princeton was the launching point for the Bethel Company, a group of 14 wagons pulled by 40 horses that set out over the Oregon Trail. John Pike was part of it, joining fellow street names Mercer, Bagley and Horton on a journey that led them to Year 2 of the founding of Seattle.

(Unlike me they beat the game: no dysentery, no starvation, and only one death due to cholera.)

The Bethel Company seems to be completely overshadowed by the Denny Party. There are a couple of great primary source reads online about their wagon trip west, though. Clarence Bagley was a boy on the journey and wrote his recollections in the 1920s. Also Daniel Knight Warren wrote his story at about the same time, which was published in a book in 1928.

Warren’s story in particular warrants our attention. He was a nephew of John Pike. I believe John Pike was the uncle mentioned in Warren’s story, the one who convinced Warren’s mother Amanda (Pike) Baxter to move to Princeton, Illinois and rejoin her previously abusive husband.

The abuse resumed, and Warren went to work at age 13 and then joined the Bethel Company at age 16 with his brothers to escape their step-father. Warrenton, Oregon — just south of Astoria — is named after him, and his former mansion is a registered landmark.

A bridge to sell ya

Pike and the Warren boys separated from Bethel Company in Oregon. They in turn split up, and John Pike ended up on his own in the tiny town of Corvallis. His family hopped on a ship and joined him.

There is little record of his time in Corvallis, but one anecdote popped up repeatedly in my research. A major road, the Territorial Road, was in planning through Benton County and on to the gold fields of California. Eventually this route became US Highway 99, now Oregon Route 99.

South of Corvallis the Mary’s River meets the Willamette River, which required a ferry crossing for wagon teams. In 1856 one John Pike opened a toll bridge to compete with the ferry. The county opted to buy him out and make it a public road, and Pike took the money to Seattle and rejoined his friends from Princeton, Illinois.

He did a thing

John Pike is literally remembered for one thing in Seattle.

He put his design and carpentry skill to work immediately after relocating here. In the 1860 census he listed himself as a “joiner”, a highly skilled carpenter. His son was a painter, and living with them at the northeast corner of 2nd and James were another joiner and painter who were probably employees of Pike.

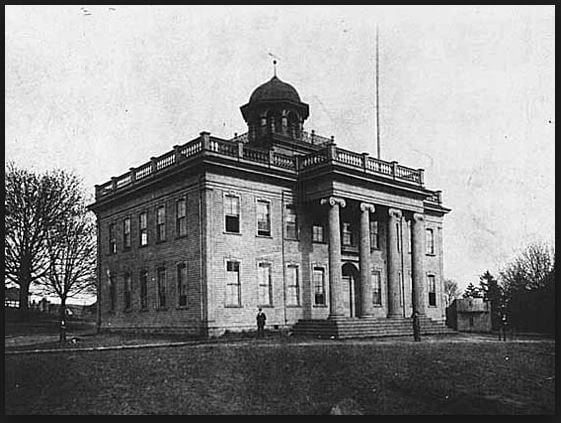

That year construction began on the Washington Territorial University in the pipsqueak town of Seattle.

John Pike was architect and builder.

Washington Territorial University, ca 1870 (Wikimedia)

(Okay, there were a couple of land acquisitions that he gets mentioned for. One involved maybe the first scheme to connect Lake Washington to Lake Union.)

There and back again and again

After the university was done the Pike family moved to Astoria, where his nephews had found success. John’s wife Helen gave birth to their second son there.

They returned to Seattle and apparently lived near what is now Pike Street prior to its official plat in 1869.

In the 1870s the family moved to Tacoma, and towards the end of his life he caught salmon for a living at Point Roberts with his son. John Pike died in 1903 on Orcas Island. He’s buried there at Woodlawn Cemetery.

His street

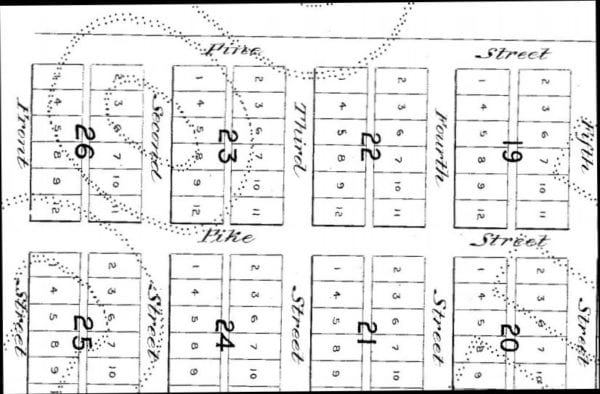

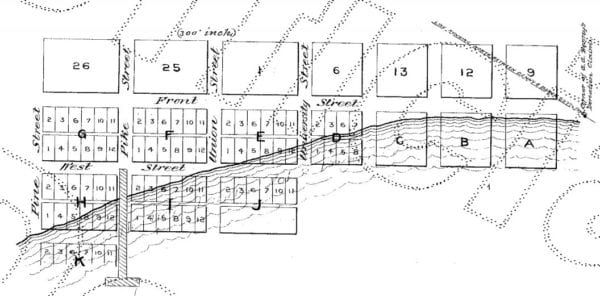

It’s not clear if Pike Street already had a name when John, Helen, Harvey and little Frank lived near it in the 1860s. It definitely had a name in 1869 when A. A. Denny labeled it Pike Street in his plat for his 3rd Addition to Seattle.

Denny cursed us with Pine Street at the same time. The absurdity is compounded in his plat, where “Pike” and “Pine” can be misread as easily as they are misremembered.

Part of A. A. Denny’s 3rd Addition to the City of Seattle plat in 1869 (King County Records)

Today Pike Street is one of the many Seattle streets that has gaps and obstructions as it makes the journey from Elliott Bay to Lake Washington. It starts on a bluff at Pike Place Market. It dips a bit to 4th Avenue and then begins a slow rise that increases as it heads east.

At Boren Avenue, Pike Street formally enters everyone’s definition of Capitol Hill and does double duty as part of Pike/Pine. After a single block it becomes East Pine and then travels east to the boundary of Capitol Hill and the Central District.

Where exactly is Capitol Hill’s eastern border? Topographically, a new hill starts at 11th Avenue, but the arterial 12th is a better boundary for that hill. Call it Renton Hill or Second Hill or maybe even Cherry Hill if you’re into that. City government draws the line at Madison Street, and there is definitely a character change across the way. So Pike in Capitol Hill is ten or thirteen blocks total.

Anyone silly enough to still think they were on Capitol Hill is woken up by Second Hill’s peak at T. T. Minor and Pike’s first dead end just prior to 19th.

Looking west on Pike from 12th. Maybe you can see the grade change up ahead at 11th. It’s steeper on this side. (Rob Ketcherside)

Up in the air

Pike Street was much higher and much lower in John Pike’s day.

The shoreline was farther east. Today’s Pike Street Hillclimb would have ended in the water.

Part of A. A. Denny’s 4th Addition to the City of Seattle plat in 1871 (King County Records)

Heading east, Pike Street skirted along the base of Denny Hill which rose up to the north. Past 4th this gave way to a ravine which rose again at Boren and continued to a steep knoll at Summit.

Here’s how I described that area when I presented the Pine Street regrade five years ago:

The Howell Plateau was a stretch of flat ground north of Howell to Denny. Below it a ravine snaked south. There was a ridge on the west of the ravine, cresting at Eighth Avenue and leading down steeply to Seventh as it dropped into the Westlake Avenue Valley. On the east was the Pike Street Hill. On Pine it had a steep cliff at Minor Avenue, but on Pike it was more gradual until a cliff at Summit Avenue. Next time you ride a 10

11 or 49bus, imagine the trolley is switching back between peaks as it turns on Bellevue Avenue.

The grade reduced but continued rising to Broadway. Another ravine bottomed out at 11th Avenue, making a clear boundary between First Hill and Renton (Second) Hill to the south.

The name Capitol Hill didn’t exist in John Pike’s day, and there wasn’t much settlement besides. To find out what it was called, read my article from a couple years back.

(While you’re indexing things to read, be sure to check out Paul Dorpat’s article about 5th and Pike from last month. He talks about John Pike and links to a bunch of other articles about Pike Street downtown.)

Terraforming Pike

John Pike almost lived long enough to see the formation of the Pike Place Market in 1907. Of course he wouldn’t know that 110 years later television audiences would watch salmon being tossed around there before sporting events.

But he lived just long enough to see his street change. If he didn’t make the trip to see it himself, perhaps his friends sent him letters describing it.

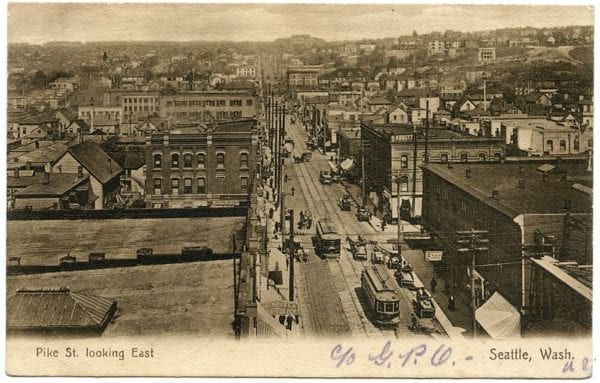

You’ve walked Pike Street to and from downtown. You know it’s steep but doable. In 1901 a feat of engineering — an offshoot of the Denny regrade — made that happen. The Pine Street regrade I wrote about before happened later, in 1907.

Pike was the first street truly opened to the back side of First Hill, to Broadway, and to all of the undeveloped land beyond.

It is absolutely not a coincidence that James Moore platted and sold lots at his new Capitol Hill addition in 1901. His advertisements raved about how many new streetcars could reach his home sites. Some of them ran on Pike Street.

Pike’s street was the portal to Capitol Hill.

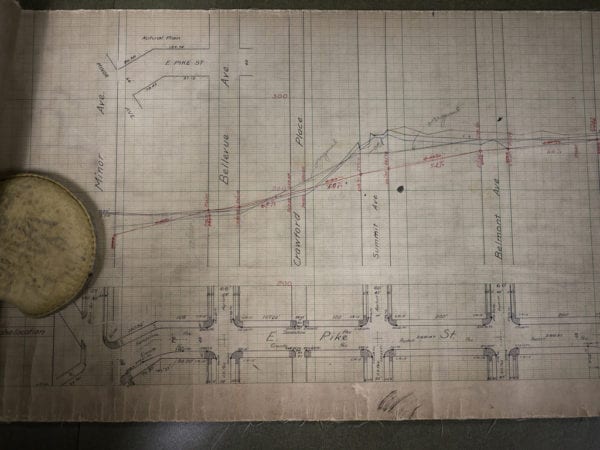

Section from Minor Avenue to Belmont of the Pike Street profile diagram of street grade change in 1901. Along the bottom is an overhead view. Above it is a cross section of what the hill would look like if you sliced straight down. Red is the new grade, black is old. Two lines for each side of the street. (SPU Engineering Vault) [Larger]

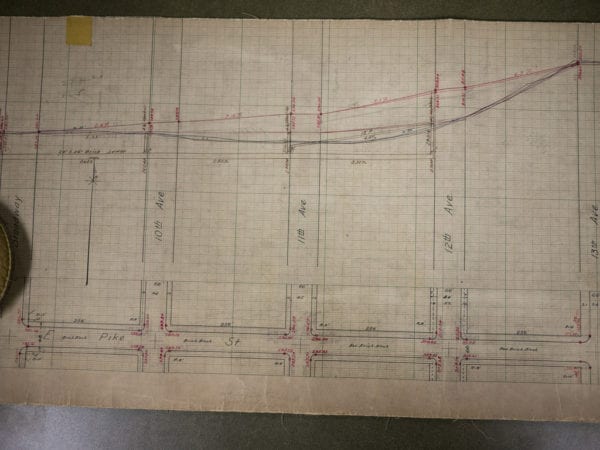

Section from Broadway to 13th Avenue of the Pike Street profile diagram of street grade change in 1901. These amazing diagrams are in one continuous cloth scroll that covers downtown to… I don’t know. I did not go beyond Madison. I might have been halfway through it. (SPU Engineering Vault) [Larger]

View from Second Avenue up Pike Street after regrade, ca 1904 (Wikimedia via me)

Very little has been written about John Pike. Beyond what I linked to above, I recommend an August 5, 1979 article in the Seattle Times by the late historian Lucile McDonald. I hope you enjoyed reading these bits as much as I enjoyed researching them.

If you want to help find and share the history of our neighborhood, join me in the new Capitol Hill Historical Society. Check our website for the next meeting time.